Written by Ichiro Irie

and published in The Fall of the Good Taste

As I have been revising E. S. Mayorga’s work and reviewing the available literature regarding it, I came by a statement in his earlier writings explaining his impulse to create and experience work that may be considered “evil” and “agonizing”. The artist refers to Edgar Allan Poe who writes, “It is a radical impulse, primitive and elemental.” Mayorga, in reference to his own work declares: “The impulse has been given a form, the form has been planned out, and the plan has been executed with complete consciousness.”

As I read this statement, I kept pondering the last two words “complete consciousness.” What does that mean, and is there really any such thing? I have always considered consciousness and unconsciousness, as ideas that exist on an ever fluctuating continuum, not unlike tectonic plates that shift and slide under the surface of appearances.

When I think of those words, I immediately think of Goya’s “El sueño de la razón produce monstruos.” The double entendre of Goya’s title raises questions of whether horrific things happen when rational thought disappears, or if horrific things happen when so called pure reason is allowed to reign freely. Such is the enigma and paradox of E. S. Mayorga and his work. On one level, his work can be seen as a self-reflexive analysis of the structures of terror. On another level, perhaps Mayorga intends his superficially innocuous work to function as objects and rituals that will really conjure evil spirits, or, at least, serve to gradually terrorize the psyches of those who experience his work.

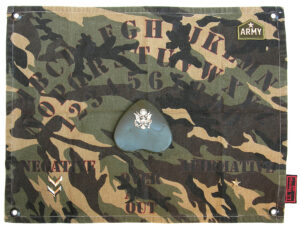

His earlier works definitely lean towards the latter. I first spoke to Mayorga at length when he was participating in an exhibition in a space I ran in Mexico City. He had explained to me at the time that his future goal was to create an object that would really elicit paranormal activity. What Mayorga exhibited at the Roma space were a series of Ouija boards with a military theme, a nursery school theme, and one in the shape of a mouse pad.

I didn’t exactly suffer from sleepless nights, but I did begin to think, “What if the Ouija boards and the other two sculptural pieces, “Object 2” and “Object 3” 2004, which looked like industrial voodoo torture devices, were the very objects Mayorga had in mind to invite the uninvited into my exhibition space?” The objects were deceptively cute and gallery friendly which may have been part of Mayorga’s scheme. Classic horror movie antagonists such as the girl from “The Exorcist” or Damien from “The Omen” begin as the very image of innocence in daily life, and by the end of the film, turn out to be the devil incarnate. This relationship between the familiar and the supernatural is exactly what provokes fear in what Freud refers to as the uncanny or the unheimlich (un-home-like).

Mayorga states that his more recent work reaches for “a more social and political structure”, and insists that each time he feels farther from examining “the personal” in relation to his obsession with the horror genre. He states: “Right now, I have concentrated more on the symbols behind the ‘spectacle of blood’,” and asks, “Why do I like this ‘show’, and in what ways does it give me pleasure, and above all, what form does Horror have?”

Mayorga states that his more recent work reaches for “a more social and political structure”, and insists that each time he feels farther from examining “the personal” in relation to his obsession with the horror genre. He states: “Right now, I have concentrated more on the symbols behind the ‘spectacle of blood’,” and asks, “Why do I like this ‘show’, and in what ways does it give me pleasure, and above all, what form does Horror have?”

To examine these questions, Mayorga is working on a project which, ironically, involves transforming himself into a monster. He describes, “The action is simple: I arrive dressed in a suit with a shovel in hand. I dig a hole in the site’s floor. I put the shovel in the hole. I cover the hole with my hands bent down on my hands and feet. I leave the site.” When he arrives at the site he is dressed very chic and acts very elegantly, but by the end of the action he morphs into a beast, savagely engaging in the absurd task of burying a shovel. In this violent action devoid of violence, Mayorga describes the mechanics of horror without overtly celebrating the pathology therein.

In another recent series, “The Fall of Good Taste” 2006, Mayorga reflects upon the work of Edgar Allan Poe, and the decadence of patriarchal values. Mayorga explains: “The house is a symbol for the family’s well being, and what he sees in the lake is the bankruptcy of the Usher family literally falling towards the abyss.” This is, for the artist, prophetic of Western civilization. “The Fall of Good Taste” is a series of maquettes of houses assembled from decorative home fixtures and burnt motor oil, which serve as a poignant critique of the relationship between the micro (the home) and the macro (global politics).

“By the way,” Mayorga adds, “these houses are also mobiles that can also be activated by paranormal phenomena.” Even the most cynical of individuals among us, in respect to the supernatural, still has the lingering doubt in the back of his mind of “What if…?” For me, it is precisely this non-erasable doubt that Mayorga and his work manage so effectively. The fact that the artist is currently in the process of deconstructing the language of terror is a commendable evolution, but this really does not completely eradicate the doubts that are manifest in the unknowable and the un-provable inherent in his work.